The following entry pivots around an incident that marked a sea change in Asa Candler, Jr.’s life, and makes visible a type of event that occurred at least three other times over the years.

While previous entries present the research as objectively as possible, this story requires speculation. Viewed in isolation the reported facts may seem incidental and hardly remarkable. But viewed within the context of Buddie’s whole life, the facts lead to the conclusions I’ve included below. I will indicate where I’ve formed opinions, and provide rationale as an invitation to consider their validity. I welcome the thoughts of anyone who familiarizes themselves with the life of Asa Candler, Jr. and draws their own conclusions, even (perhaps especially) if they contradict mine.

Let’s get started.

Asa Jr’s Inman Park Home. To the far right of the photo a ventilation cap is visible on top of the roof of what was likely his garage.

First a quick summary of the events leading up to the incident:

Following a tumultuous childhood and education, Asa Candler, Jr., went to Los Angeles and then Hartwell, GA, to run pieces of his father’s business. After these ventures failed he moved home to Atlanta, and in 1908 he moved to a permanent home in Inman Park. He dabbled in tontine insurance and wire house gambling, and established a side hustle selling discounted coal during the warm months of the year. He briefly took a shot at running for city council against his family’s wishes. And his position as the building manager of the Candler Building put him in a prominent role that ran in the same circles as the big names in Atlanta business.

In 1909 he conceived a grand plan to build the Atlanta Speedway and convinced his father of its profit potential. In what is in hindsight an obviously risky decision, Asa Jr. committed to an accelerated construction timeline and a set of luxury features that skyrocketed the total build cost. His business partner, Ed Durant, was an insurance man who taught Buddie to put a protective policy on everything, including one that protected their investment from a rain-out. During the November inaugural races, Asa Jr.’s special racing car burned to char, but an insurance policy prevented the property loss from becoming a financial loss. Huge crowds made impressive headlines, but he failed to recoup the cost of construction, leaving a debt of $130k in its wake with no upcoming races in the immediate future.

In December of 1909, Asa Candler, Sr. engineered a transaction that divested himself of the risk associated with the Speedway and transferred the debt to Buddie’s personal holdings. This made Buddie indebted to his father to the tune of $130k. The mortgage was scheduled to come due in December of 1910, so that gave him one year to get the venue operating in the black. But a series of unsuccessful races with underwhelming attendance failed to bring in the revenue needed to offset the outstanding balance. By December of 1910, the track’s fate was sealed. Recouping the debt was too unlikely. Its closure was imminent.

throughout 1909 and 1910 Buddie struggled to control his public reputation, grappling with gossip and what appears to be a deep insecurity about his value, or the perception of his value, while standing in his father’s immense shadow. In the thick of the falling out with Ed Durant, he made statements to several sources stating that he had secured land in his father’s soon-to-be-elite neighborhood of Druid Hills. He claimed to be working on a plan to build a $100k home, which was a monstrous price tag for the time.

We have no direct quotes from Buddie, so we don’t know the terms he personally used to describe the project. What we have are reports of his expressed intentions. The Atlanta Journal claimed an inside source told them that Asa Candler Jr. was abandoning his plan to build a $100k “palace” due to the Speedway uproar. Whether Buddie said palace, the source said palace, or the Journal chose the word palace is unknown. But we can infer from its usage that his reputation at that point made the word sound plausible to the paper’s readers.

As evidenced by public statements, paid press, and purchasing habits, Asa Jr. placed importance on the perception of himself as a successful, wealthy businessman. Far more than his brothers, he thrust himself into the public eye again and again with carefully crafted—and sometimes demonstrably false—narratives about his success, skills, and popularity. He spent all of 1910 trying to rebuild his reputation, but the track’s failure to succeed tanked the public’s perception of his business acumen.

In January of 1911 he made a last effort to capitalize on his small celebrity, and by extension the track. He shopped around a story about his son John driving his Lozier Briarcliff, invoking the legacy of the car that had won him some national press in mid-1910. In February of 1911 there was still no indication that the $100k palace in Druid Hills was in the works, and he and his family were still living in their home in Inman Park. Sometime in the year since he announced his land purchase, his plans to move had been stymied.

When his name next showed up in headlines, it wasn’t about his real estate plans.

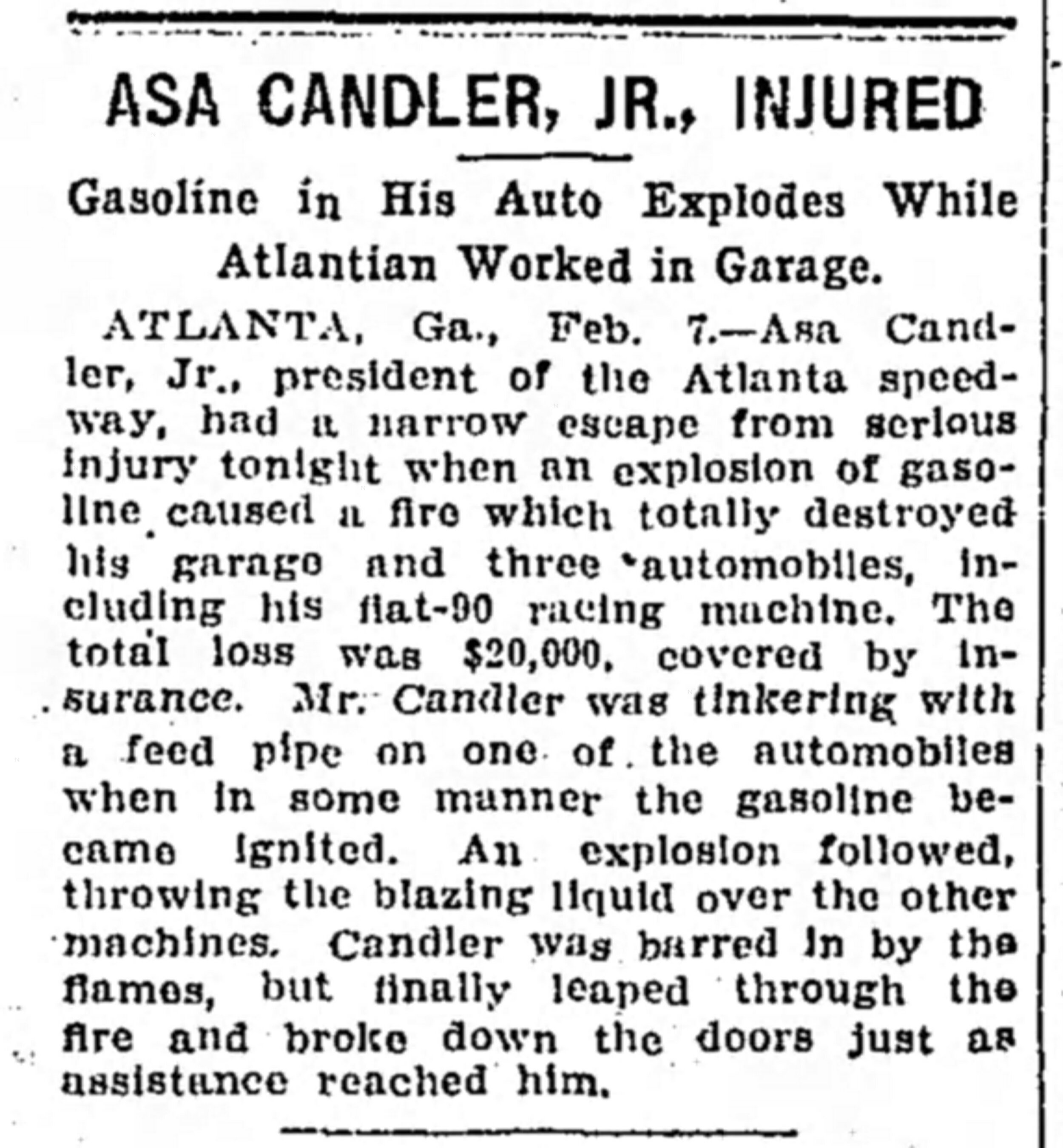

The Tennessean, February 8, 1911

The First Fire

On the afternoon of February 8, 1911, Buddie went out to his garage to work on one of his cars. He lit a blowpipe and started cutting into a clogged gas line. The fuel in the tank caught fire and blew, scattering flames around the garage. Cornered by the rapidly spreading blaze, Asa Jr. leapt across the burning floor and escaped.

Fire crews responded and prevented the flames from spreading to the main house or neighboring properties. But the garage was destroyed, along with three of his five cars. The big red Fiat, a Pope-Toledo, and his racing Renault were burnt beyond repair. Not included in the inventory of damaged vehicles was his limousine, which was parked up by the house, and his beloved Lozier Briarcliff. Either the Briarcliff survived or was no longer in his collection by then. For all of its celebrity, it’s mentioned nowhere in any of the national press coverage of the incident.

Asa Jr. suffered some mild burns, and I’ve noticed that he started showing up in photos with a cane after the 1910s. Perhaps a result of injury from this incident. But otherwise he was fairly unscathed, given the scale of the event.

Although reports varied slightly across several newspapers, nearly every account included one consistent detail: The lost property was insured for a total of $20k, which adjusts to about $500k in 2019 dollars. Then, sometime between the explosion and June of 1911, Asa Jr. found the funds to complete his Druid Hills transaction and moved his family out to the new property and into the existing farmhouse that already stood on the land.

In March and April, Asa Jr. distracted himself from the Speedway’s failure by throwing his support behind his father as Coca Cola faced a serious legal challenge in Chattanooga, TN, in what is known as The United States Government vs. Forty Barrels, Twenty Kegs Coca-Cola. He rounded up witnesses to testify on Coca Cola’s behalf and ran them back and forth between Atlanta and Chattanooga, ensuring that his family’s business could demonstrate the harmlessness of their product as the government tried to prove otherwise. Read more about the trial here.

In May, Asa Jr. made a lukewarm statement about the AAA trying to arrange a race that didn’t seem likely to happen, and indeed never did. In June, a man named William Walthall purchased and moved into the Inman Park house. So Asa Jr. and his family were definitely out by then.

In October of 1911, Asa Jr. was scheduled to drive cross-country in his Lozier Briarcliff in the Glidden Road Tour, but cancelled at the last minute, citing illness. Either he was unfit for the job, or the Briarcliff was. Either way, the infamous Lozier was never mentioned again.

A year later Buddie’s new property started showing up in advertisements listed as Briarcliff Farm.

The Atlanta Constitution, November 3, 1912

This is where the speculation begins.

Asa Candler Jr. had a distinct pattern that manifested several times throughout his life. His nine-step cycle went as follows:

Make a grand, publicly visible endeavor

Get some positive press regarding its success

Build momentum and attention with outlandish features and investments

At the peak of the hype, make several expensive purchases in rapid succession

Flounder within a year

Misrepresent and distract with hyperbole and lies

Liquidate assets in rapid succession and abandon the venture

Go quiet for a little while

Start the cycle all over again with a grand, new financial spend

In a previous Atlanta Speedway entry I shared a glimpse of this cycle as it preceded the acquisition of his Lozier Briarcliff. You see it play out in the mid to late 1920s, during the early to mid 1930s, and during the 1940s. More stories will be shared in future updates that detail the exact events around each cycle that parallels this one.

So why do I see this as the first example of Asa Candler, Jr.’s cycle? Well, what do we know about Buddie’s situation in 1911? We know he demonstrated a buying, hyping and selling pattern that recurred later in life around similar financial upheavals. We know that Asa Sr. put the debt of the Atlanta Speedway in his son’s name. We know that the press dragged Asa Jr.’s name and reputation through the mud, and one of the few statements he made in response was to claim he was busy building an impossibly expensive mansion in Druid Hills. We know that Asa Sr. foreclosed on the track in early 1911 when Buddy’s real estate deal was still finalizing, and that foreclosure meant no chance of future events to bring in income to offset his debt. He progressed from step 1 to 6 of the above outlined cycle between 1909 and 1911.

We know that when he moved his family out to Druid Hills there was no big mansion waiting for him. And we know he didn’t break ground on his “palace” for another decade. But he did manage to complete the transaction and within a year he was able to start advertising Briarcliff Farm. So that’s steps 8 and 9, with Briarcliff Farm bringing him back around to step 1.

We know that in February of 1914, Asa Sr. bought the foreclosed Atlanta Speedway land back at a sheriff’s auction for $1000. We know that he obtained a judgement of $130k on his civil lien against the AAA, which we learned from the contract on file at Emory University was actually debt owned solely by Asa Jr.

The Atlanta Constitution, February 4, 1914

So the debt was not resolved between the 1911 foreclosure and the 1914 judgement lien by Asa Sr. We also know from family lore that when Asa Sr and Lucy Elizabeth gave their kids their inheritance in 1916, Asa Sr. balanced his books and deducted any outstanding debt from each child’s portion. Famously, Buddie’s debt was reported as $100k. If he was indebted to his father, where did he get the money to complete his Druid Hills transaction and move his family out to the farmhouse?

Step 7: liquidate assets.

The track was a failure, and he had no other ventures that were big enough to resolve the debt. It wouldn’t help to sell off the track, because any money made from the sale would go to his father. If he wanted to follow through on his 1909 claim that he was moving out to Druid Hills, he had to free up funds some other way.

I suspect the Lozier Briarcliff was sold off as the first casualty of step 7. He bragged to the press about its performance in January, then in February it appeared nowhere in the coverage of the garage fire. His claim of illness that forced him to cancel his participation in the Glidden Tour was likely a cover story. He couldn’t drive his Lozier in the Glidden because he didn’t own it anymore. So he likely liquidated his prized vehicle as part of step 7.

After scrutinizing the various accounts of the garage fire, I find some of the details suspect. Buddie was an early adopter of automobiles. Purchase records demonstrate that he performed his own maintenance on his cars from the beginning. He owned a variety of cars, and transitioned from steamer to internal combustion engine as soon as gas powered cars hit the market. And anyone who raced knew the risk of gasoline igniting. Why would someone so knowledgable about cars and engine maintenance use a blow pipe to cut a fuel line on a car that still had fuel in the tank? It could have been a lapse of judgement. It could have been a known risk, made with the assumption that the clog in the line would prevent the vapors from catching. But I don’t think either of those options is likely.

I believe Asa Jr. set the fire and intentionally burned his collection and garage. After all, with the track going belly up, he had no use for racers anymore. The Atlanta community had turned racing into a humiliation, which made the collection a personal liability. Selling off the whole collection just when the track was visibly failing would have also been embarrassing, which is why I think he kept the sale of the Lozier Briarcliff quiet. But a fire, that would turn the cars in to cash quickly, without having to expose his need for cash to the community.

As mentioned, he started out in tontine insurance, which was a rigged pyramid scheme that made investors rich while the policy holders paid into funds they’d rarely benefit from. Ed Durant showed him the ins and outs of property insurance, so he was well familiar with the way insurance could be cashed in to prevent financial losses. And insurance fraud by fire was commonplace. It’s no difficult task to find scholarly articles studying the increase of insurance fraud due to arson during recessions. In fact, it’s such a long-standing practice that the Roman poet Martial wrote a short quip about it way back in the first century AD:

“Tongilianus, you paid two hundred for your house;

An accident too common in this city destroyed it.

You collected ten times more. Doesn’t it seem, I pray,

That you set fire to your own house, Tongilianus?”

For a wealthy man whose money was mostly tied up in investments and real estate, the extravagant toys that facilitated his life of leisure could be put to use when their utility came to an end. The track had come to an end, driving as a fun and exciting hobby had come to an end, and the utility of his racers had come to an end. Why not let them burn? While this may seem like a leap to assume he held such a cynical view of the track and his car collection, we get a glimpse into his mindset in 1915.

After Asa Sr. reacquired the land in 1914, he briefly considered using it for the Emory College relocation that his brother Warren Candler wanted. The community of Hapeville put some effort behind the campaign to bring the Methodist college there, but ultimately Asa Sr. chose to donate a section of Druid Hills in 1915. When reached for comment, Asa Jr.’s response demonstrated a bitterness that leaked into the reporter’s brief blurb.

The Oakland Tribune, May 2, 1915

So I leave it now to you, the reader, to decide what you believe happened in February of 1911. Did Asa Candler, Jr., suffer an accident of pure happenstance? Or was this an example of insurance fraud by arson, following a financial crisis brought on by his crumbling business venture? Perhaps you’ll conclude that it was all a coincidence. Perhaps you’ll believe that this is a cynical interpretation of events seen through the haze of an incomplete historic record.

But perhaps when you read about the other fires you’ll change your mind.

More to come in future updates.